Alamance County Remembrance Coalition Sheds Light on a Dark History

Handheld candles light up the night outside the Grahm County Court House on Feb. 25, the eve of the 154th anniversary of the murder of Wyatt Outlaw.

During the reconstruction, Alamance County contained significant cases of anti-Black violence. Embedded in that history lays a story of unparalleled Black achievement with a tragic ending.

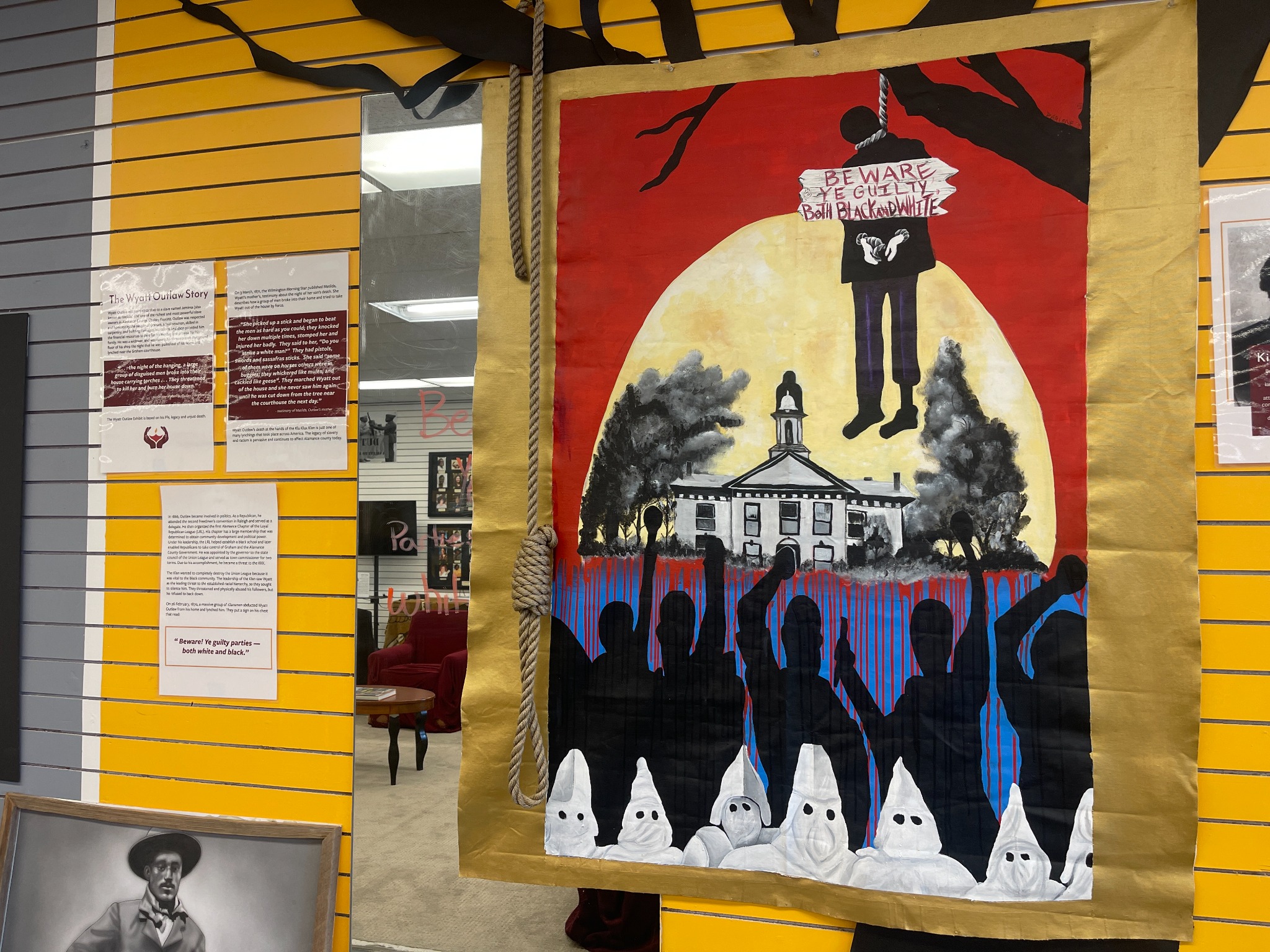

Outlaw was the first Black town commissioner, a town constable, a Union League organizer and a small business owner. In his role as president of the Alamance County Union League of America, he stood against the KKK’s presence in Graham and advocated for a school for Black students.

On the night of Feb. 26, 1870, Outlaw was taken from his home by a group of 60 hooded Klansmen to the Graham County Court House, where he was hung. Around his neck lay a warning for anybody who wanted to take a stand against the KKK in Alamance, “Beware! Ye guilty parties – both white and black.”

The vigil on Feb. 25 hosted by the Alamance County Remembrance Coalition attracted nearly 70 attendees. This was the fifth consecutive year that the coalition hosted a vigil to remember Outlaw.

Formed in 2019, the coalition is part of the Equal Justice Initiative, a non-profit based in Montgomery Alabama. EJI works to explore “our nation’s history of racial injustice” as part of their commitment to changing the narrative about race in America, according to their website.

The site also states that as a country, “We must truthfully confront our history of racial injustice before we can repair its painful legacy.”

One specific way in which EJI works to confront the history of racial violence in communities is through soil collection, as seen within Alamance County.

A collection ceremony, held in Jan. 2023 honored the life and legacy of Outlaw by gathering soil from the site of his lynching. Following the collection, the coalition is able to bring this sacred ground to people in order to foster community conversation and reflection.

Coalition member Dr. Sandra Reid believes that reconciliation is necessary to build true community.

“I feel like if we were to ever be able to come together completely in a community, we would need to reconcile these things that have gone on,” Reid said.

Reconciliation begins with nights like Feb 25, when community members engage with the hard parts of Alamance’s past.

Soil jars collected from the site of Outlaw’s lynching were on display for attendees to see and interact with throughout the night.

According to the coalition’s site, they have four main goals, including community education, soil collection, the erection of historical markers and finally, bringing a lynching memorial to Alamance.

Soil collected by the Alamance County Remembrance Coalition from the sites of John Jeffress' and William Puryear's murders sit on display in the African-American Cultural Arts and History Center. Video By Audrey Geib

Soil collection ceremonies were also performed for the deaths of both William Puryear and John Jeffress.

William Puryear was killed by members of the KKK after he pursued some of the men responsible for the death of Outlaw. After a confrontation between Puryear and the men, Puryear disappeared, however, his body was later found, bound and weighted in a mill pond.

Although the exact date of Puryear’s death is not known, his body was reported on June 1, 1870.

The papers that released the information about the finding of Puryear’s body did not include explicit locations of the mill pound, but the coalition was able to find it with the help of historian Dr. Carol Troxler.

Troxler authored a book titled “Shuttle & Plow: A History of Alamance County, North Carolina” in 1999, which later led her to research and publish a biography on Wyatt Outlaw titled “to look more closely at the man” published in 2000.

An academic article detailing the life of Wyatt Outlaw, written by Dr. Carole Troxler published in 2000.

It was due to this research that the remembrance coalition sought out Troxler and her knowledge. Finding the pond required alot of sorting through various histories and documents from that time. Troxler said that a portion of what went into finding the pond was serendipity.

“I had about given up on finding that pond," Troxler said. "I had been working just on finding that pond for four months for the coalition. Finally, I said, ‘You know, I just don’t think that we’re going to be able to do this' and we were talking about alternative places for Mr. Puryear. Like where he was in Graham when he saw the people take Wyatt Outlaw out of his house, that was kind of our next step, and then serendipity came in.”

Reid emphasized the impact that soil collection had on her specifically and how it can impact others.

“Just digging that soil, knowing that this is where this happened, and reflected on that. It's quite powerful,” Reid said.

The coalition takes the collected soil jars to various community groups throughout Alamance to engage members in the history of racial violence.

The next step the coalition wants to take is the erection of historical markers commemorating the men who lost their lives due to acts of racial violence. But before the coalition can partner with EJI to apply for markers, Reid said that the coalition is looking to host a big community event.

“In the meantime, we are trying to plan a community event that will allow us to be in Graham, in that area, to have focus groups where community folks can gauge how they see this history, gain more information, and hopefully bring a coalition of different community members together,” Reid said. “So that's our plan is for a huge community event, like a walking tour of Graham.”

Post a comment